- Acquire a broad outline of how children develop language skills.

- Explore some of the psychological and linguistic theories surrounding the acquisition of language.

- Examine some ways in which language continues to develop through the teenage years into adulthood.

- Look at suggestions as to why language itself evolves over time.

| Session 1 |

| |

Naming Names

ET, the well-known Extra-Terrestrial, learnt human language fast: 'His ear-flap opened and he listened intently ... His ... circuits buzzed, assimilating, synthesizing ... Thus inspired, the language centre of his marvellous brain came fully on ...' Yet ET's magical ability is almost matched by that of human children. As the American statesman Benjamin Franklin once said: 'Teach your child to hold his tongue; he'll learn fast enough to speak.'

|

| Jean Aitchison |

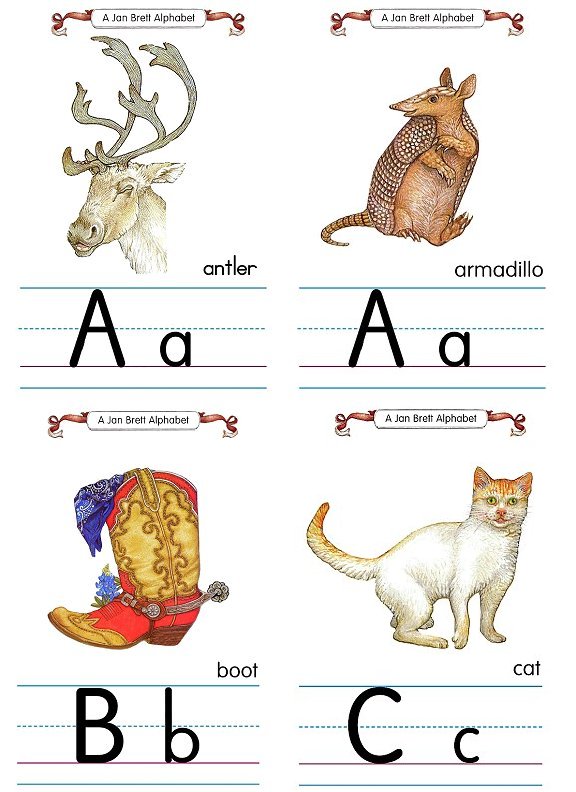

| Figure 1. Typical speech timetable for an English-speaking child. |

Children talk so readily because they instinctively know in advance what languages are like. As in a spider's web, the outline is preprogrammed, and the network is built up in a preordained sequence. The predictable way in which the language web develops is the topic of this seminar, including how adults can help, or sometimes even slow down a child's progress.

Language has a biologically organized schedule (see Figure 1). Children everywhere follow a similar pattern. In their first few weeks, babies mostly cry. As Ronald Knox once said: 'A loud noise at one end, and no sense of responsibility at the other.' Crying exercises the lungs and vocal cords. But crying may once have had a further evolutionary purpose. Yelling babies may have reminded parents that their offspring exist: deaf ringdoves forget about their existing brood, and go off and start another.

From six weeks onwards, infants coo or even mew according to some older accounts, which sometimes compared these early gurgles to the twittering of birds. From around six months, babies babble language-like sounds. 'He called me mummy' is a typical squawk of a delighted new parent, as a child exercises its mouth with the sequence ma-ma-ma or da-da-da. Over-interpretation by parents is why the words mama, papa and dada are found all over the world for 'mother' and 'father', closely followed by kaka for 'excrement'.

A widespread myth circulates, that infants burble all sounds of every language. This is untrue, the range is in fact rather limited. The myth arose partly because some early researchers found it hard to distinguish early infant gurgles, and partly because children do indeed produce some sounds not found in the language they are learning. But a babbling drift takes place, in which children gradually veer towards the sounds found in their own language: Chinese babies are reported to babble single syllables with different tones.

Single words 'Oo! Da!' are produced from around the age of a year. Parents often play naming games with youngsters: they point to a black fluffy blob in a book and say 'cat'. Little Bobby or Suzy imitates, saying maybe ga. The discovery that ga is a name for the dark splodge comes later. Children do not at first realize that sounds can be labels for things. Early words are tied strongly to a location, and often relate to a whole scene. A word da for a toy duck might be for one particular duck as it floats in a particular bath. Only later will da be used for a duck away from the bath, and later still extended to all ducks, and maybe swans, geese--and even toy boats.

The naming insight, the discovery that things have names, is a major leap forward. Children pass this milestone at various times, typically before the age of eighteen months. Parents don't usually notice it, it seems so normal, because adults expect things to have names. But for youngsters, the naming discovery can be a shock, as shown by occasional children who come to it late. Helen Keller was deaf and blind from the age of two. Then, when she was six, her teacher held her hand under a flow of water, and spelled out the word w-a-t-e-r on the other. She later wrote: 'Somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that "w-a-t-e-r" meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul.. ., set it free! . . . Everything had a name, . . . every object which I touched seemed to quiver with life.' |

| Session 2 |

| |

Innate Abilities

The naming insight is followed by a 'naming explosion'. Names come popping out of children like stars out of fireworks. This eruption in vocabulary leads to word combinations, mummy push, daddy car and so on. Some phrases are novel, as byebye sock, allgone kitty, which are unlikely to have been copied from adults. Recurring patterns are found as with sand toe, 'I've got sand in my toes', sand eye 'I've got sand in my eye', and sand hair 'I've got sand in my hair'. The parents were probably too busy mopping the sand off this child to admire the consistency of its language rules.

| |

| Jean Aitchison |

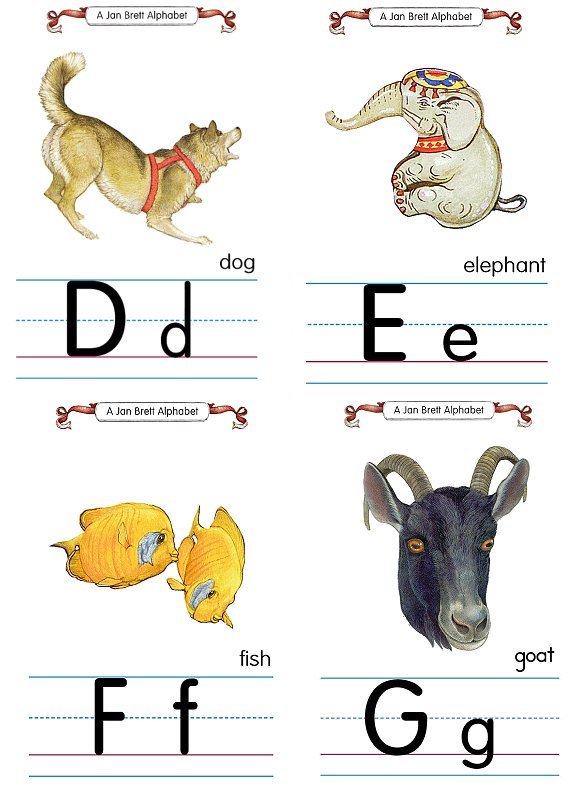

| Figure 2. Innately guided behaviour. |

Youngsters look for regularities in language, as shown by the wug-test, devised by Jean Berko Gleason in the 1950s. 'Here is a wug', she said, showing a picture of a bird-like creature. Then she showed two of them: 'Now there are two...' 'Wugs' responded children from a very young age.

Children do not always get it right first time. Two-year-old Sophie learned the words broken, fallen and taken. She wrongly concluded that English past tenses end in -en. She then invented a whole range of new past tense forms, such as boughten, builden, riden, gotten, cutten, wanten, touchen, maden, tippen, as in 'me tippen that over'. Sophie gradually dropped these -en forms--probably when she discovered the normal past tense for each verb. Children dislike finding two words which mean exactly the same thing, and usually drop one of them.

By the age of three, children utter long sentences, though some things, such as pronouns, still cause problems. Three-year-old Adam said his doll 'shuts she's eyes', instead of 'shuts her eyes'.

At around three and a half, children talk freely. By this time, they have acquired most of the constructions used by adults. This is true of monolingual children, and also bilingual ones. A few gaps still exist for all children up to the age of around ten, and word-learning goes on throughout life.

This predictable sequence of events is typical of biologically scheduled behaviour, as pointed out by Eric Lenneberg, a pioneer in this field. His book Biological foundations of language, published in 1967, was a major landmark. Before then, natural behaviour, such as seals swimming, was usually separated from nurtured or learned behaviour, as when seals can be taught to jump through hoops.

Lenneberg showed that this divide is over simple. Most natural behaviour requires some learning: pigeons naturally fly, but they have to spend time learning how to stay in the air. Conversely, learning would be impossible if it did not build on natural talents: pigeons can be trained to distinguish between letters of the alphabet, but only because they already have acute eyesight.

Language is an example of maturationally controlled behaviour, Lenneberg pointed out, behaviour which is preprogrammed to emerge at a particular stage in an individual's life, provided the surrounding environment is normal. Walking and sexual behaviour are other examples. Such behaviour emerges before it is critically needed, yet cannot be forced to appear before it is scheduled. Some learning is required, but the learning cannot be significantly speeded up by coaching. No external event or conscious decision causes it, and a regular sequence of milestones can be charted.

An ability to cope with language structure is largely separate from general intelligence. In recent years, several so-called 'cocktail party chatterers' have been discovered--children who have a non-verbal IQ so low that they may not even know their own age, but who speak fluently. As at cocktail parties, they talk for the sake of talking, and their speech may not make sense. Take Laura, an American teenager: 'I was sixteen last year, and now I'm nineteen this year' or 'It was no regular school, it was just good old no buses.' Such chatterbox children are not just repeating set phrases, because they make grammatical mistakes which they are unlikely to have heard, as in Laura's statement that 'Three tickets were gave out by a police last year.'

Just as bees learn fast to distinguish flowers from, say, balloons or bus-stops, so human children are preset by nature to pick out natural language sounds: they do not get distracted by barking dogs or quacking ducks. Their learning is innately guided (see Figure 2). Inbuilt signposts direct youngsters, so they instinctively pay attention to certain linguistic features, such as stressed vowels and word order. Children's main task is to discover which of these features have priority in the language or languages they are acquiring, just as bees have to learn whether to look for heather, roses or lilies. |

|

| Session 3 |

| |

Leaps of Language

A biological time-clock ordains the sequence in which the language web is woven, though not the exact dates. But nobody is quite sure when the clock starts ticking, and when it stops. According to Lenneberg, humans are scheduled to acquire language within a critical period between the ages of two and thirteen, a time preordained by human nature. After that, the acquisition of language was difficult, he claimed, maybe impossible.

Lenneberg turns out to be partially wrong and partially right. He is wrong about the starting-point. Language acquisition begins well before the age of two. Babies only a few days old can pick out their own language, according to some research by Jacques Mehler and his colleagues in Paris. The infants responded to French with increased sucking movements, a standard reaction to sounds which interested them. But they did not display the same reaction to other languages. So infants still in the womb may become accustomed to the rhythms of the language spoken around them.

And language development does not come to a shuddering halt at adolescence, as Lenneberg assumed: vocabulary even undergoes a spurt at this time. So the idea of a fixed critical period is now disputed.

Yet most people find it easier to learn languages when they are young--so a sensitive period may exist, a time early in life when acquiring language is easiest, and which tails off gradually, though never entirely.

A 'natural sieve' hypothesis is one idea put forward to explain this. Very young children may extract only certain limited features from what they hear, and may automatically filter out many complexities. Later learners may have lost this inbuilt filter, and be less able to cope as everything pounds in on them simultaneously. A 'tuning-in' hypothesis is another possibility. At each age, a child is naturally attuned to some particular aspect of language. Infants may be tuned in to the sounds, older children to the syntax, and from around ten onwards, the vocabulary becomes a major concern. Selective attention of this type fits in well with what we know about biologically programmed behaviour.

|

| Jean Aitchison |

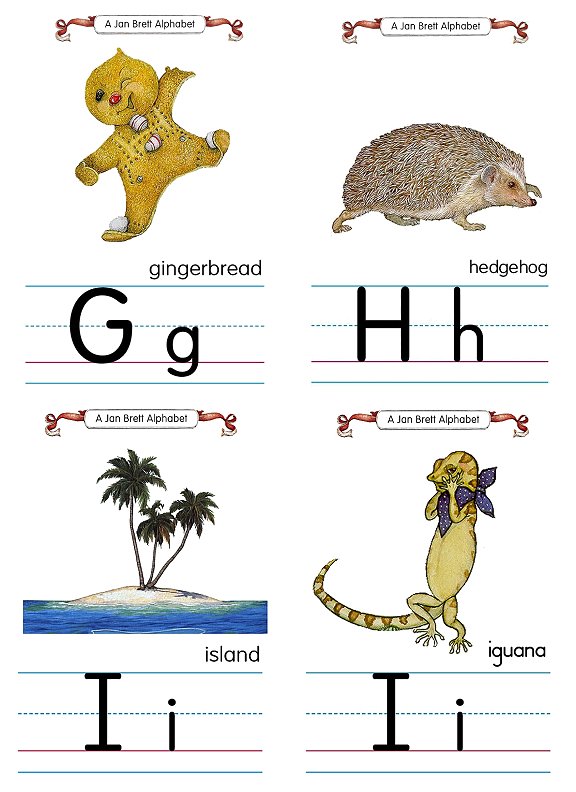

| Figure 3. Chomsky's switch-setting. |

The outlines of the language web are therefore preordained. Acquiring language involves weaving in the network details of one's own native tongue, with particular portions scheduled to be filled in at particular ages.

Japanese, Welsh or Samoan--children handle all languages with equal efficiency. The American linguist Noam Chomsky has suggested that children might be innately endowed with advance information on the main ways in which languages can vary. So children may have to discover whether they are dealing with an English-type language, which puts verbs in front of its objects, or a Turkish-type one which does the reverse. Once a decision is made, the child metaphorically 'sets a switch', with multiple repercussions. If, as in English, a language has verbs before its objects, as in climb the tree, then it will also probably have prepositions before nouns as in up the tree. A language such as Hindi or Turkish would have the reverse, and say, as it were, the tree climb, and the tree up. It is as if the child was sitting in a linguistic bath, and watching which way water swirled down the plughole, clockwise or anti-clockwise. Once the youngster had found this out, then it would automatically know the linguistic equivalent of whether it was in the northern or southern hemisphere, and whether days got warmer to the north or to the south. In technical terminology, children 'set parameters', a mathematical term for a fixed property whose values vary (see figure 3).

Chomsky makes acquiring language sound like turning on a light, more instantaneous than it really is. But his theory rightly emphasizes that any language holds together in a network of implications. If a language has one type of construction, others are predictable from it.

But natural web-spinning can be both helped and sometimes hindered by the speech of those around. Early research talked of motherese, mother's speech. This left out fathers and friends, so caretaker speech became the fashionable term, later amended to caregiver speech, and in academic publications, to CDS 'child directed speech'. I'll leave it at caregivers. Another term 'baby-talk' is best avoided, because it usually refers to gee-gee, puff-puff, moo-cow-type words, so puzzlingly widespread in England when talking to babies or sending Valentines.

Caregiver speech can be odd. Some parents are more concerned with truth than with language. The ill-formed 'Daddy hat on' might meet with approval, 'Yes, that's right', if daddy was wearing a hat. But the well-formed 'Daddy's got a hat on' might meet with disapproval, 'No, that's wrong', if daddy wasn't wearing a hat. You might expect children to grow up telling the truth, but speaking ungrammatically, as some early researchers pointed out. In fact, the opposite happens.

Parents also reportedly care about etiquette: 'Say please', or they pick on swear words: 'Don't let me hear you say that word again', or they notice occasional pronunciation problems: 'Say Trisha, not Twisha.' If they do pick on language formation, it's often verb endings: this may be useful, if the child is tuned in at that time to learning these. If not, the correction is likely to be ignored. One much-quoted conversation was about baby rabbits:

'My teacher holded the baby rabbits, and we patted them', said the child.

'Would you say she held them tightly?' asked mother.

'Oh no, she holded them loosely', replied her daughter. At best, a sensitive parent provides support, by being aware of structures to which the child is attuned. Mostly, parents muddle along, sometimes getting it right, sometimes wrong. At worst, a grumbling tone of voice can sap confidence: a child may realize that something is wrong, but not always know what. Only talk directly addressed to the youngster has an effect. Vincent, a hearing child born to deaf parents, learned to communicate with sign language. He himself could hear, and he used to sit in front of the television, and watch the pictures with fascination. But apparently, he did not pay any attention to the sounds. He did not start to speak until he went to school, where people talked to him. And a recent survey in Manchester found that television can delay speech development even in some normal children: they are riveted by the colours and flashing lights, and tune out the sounds. |

| Session 4 |

| |

Ongoing Development

But even with face-to-face contact, the young learner sets the agenda. Clear, varied utterances directly addressed to the youngster are the silken strands out of which the child builds the language web. Caregiver speech is extra-useful when the same words come in more than once in different ways. Many parents do this naturally: 'Now Patsy, where did you get that knife? Give the knife to mummy. Give mummy the knife. There's a good girl.'

|

| Thinking Points |  |

|

- Does language serve a different purpose in childhood than it does in adult life, or is children's language simply a stage in development towards maturity?

- Is language always about communication between individuals, or is it possible that a child could develop a language unknown to anybody except him- or herself?

|  |

|

The talk has to grab the child's attention. Joint enterprises are all important. Research published around ten years ago showed that parents found it easier to talk to girls, mainly because they involved them more often in domestic chores: 'Come and help mummy with the potatoes', mothers tended to say to their daughters. But 'Go outside and play football', they commanded their sons. Not surprisingly, some families ended up with chattering potato-peeling girls, and tongue-tied football-kicking boys. This was one reason why girls were often a step ahead of boys in their language, it was suggested. Hopefully, this imbalance is being corrected, with both sexes now equally involved in chores, and perhaps equally acquiring language.

But if people talk to them, all children respond well. They enjoy pit-patting the conversational ball backwards and forwards. 'Put on your coat', said father. 'Why?' asked junior. 'Because we're going out.' 'Why?' 'Because we're going to buy some dinner.' 'Why?' 'Because we have to eat.' 'Why?' At this point, father realized junior was not interested in the answers, but was treating the conversation as a game, which he wanted his father to go on playing.

So children build the language web by extracting what they need from the talk they hear around them. Most are efficient chatterers long before they go to school. But they still need to learn which type of speech to use when--so-called 'communicative competence'. In linguistic terminology, different registers suit different occasions. Babies and bank managers must be addressed in different ways, just as different clothes are required for the beach and a wedding. A doctor speaking to another doctor might talk about a circumorbital haematoma, but to a schoolboy, it would be a black eye.

The language web, then, has been mostly acquired by children by around the age of thirteen, apart from the mixing and matching of language styles, and also vocabulary.

You might expect parents to cheer as their offspring become competent language users, and give them, say, a reward of a telephone on their thirteenth birthday. But the acquisition story is not yet over. At this age, language suddenly becomes a mudslinging match between generations. Teenagers want to talk like their pals, but parents disapprove. A father was shocked when his daughter informed him that she did not dare talk in her 'posh' home voice at school; she would lose her friends.

Teenage stroppiness is partly to blame, with predictable kicks at convention--though this is normally a temporary phase. Teenagers' language usually gets less extreme as they approach adult life.

But changing speech styles also tangle people up. These days, formal speech, like a top hat, is used on fewer occasions. Informal speech, like an open-necked shirt, is felt to be friendlier. In this easy-going atmosphere, being 'proper' is often regarded as less important than being 'matey'.

Matiness and casualness are sometimes emphasized by swearing. Swearwords swarm like bees in some recent literature, and buzz about freely in conversation. Yet today's swearwords are undergoing a bleaching process, a fading of meaning that happens in all semantic change. In the last century, oaths using the name of God were widely disapproved of. Then they gradually lost their power to shock. These days, f-words (sexual swearing) and s-words (excrement-swearing) no longer horrify so many people. Their meaning has weakened as the original connection with sex and excrement fades.

But the war of words between the generations is also entwined with the usual cobweb of worries which surround language change. Parents want their offspring to use so-called Standard English. What exactly they mean by this is a question which has long ensnared people in its sticky and dusty threads. The word 'standard' is ambiguous: it can mean either a value which has to be met, as in 'a high standard', or it can mean uniform practice, as in 'standard behaviour'.

These two meanings of standard have long been confused. For example, in 1836, a treatise which offered 'principles of Remedy for Defects of Utterance', commented that 'the common standard dialect is that in which all marks of a particular place of birth and residence are lost and nothing appears to indicate any other habits of intercourse than with the well-bred and well-informed, wherever they may be found'.

So Standard English came to be thought of as the speech of the educated. This was often assumed to be the language of Oxford, so-called Oxford English, and of the most expensive fee-paying schools (known in England as 'public schools'). So the word 'standard' moved from meaning general usage to that of a specific group to be emulated.

But it's important to distinguish between accent, which describes pronunciation, and dialect, which involves grammar. Spoken Standard English is not an accent--as pointed out in a recent survey commissioned by the National Curriculum Council (a body which sets up school curricula in Great Britain). Pronunciation has always varied, and Standard English includes a variety of accents. Different accents are a sign of identity, a badge of one's area. They are a problem only if they are hard to understand. Meanwhile, the grammar of English is fairly similar across the British Isles. Standard spoken English is usually defined as the grammatical forms used in formal public contexts, and they do not vary very much.

But language is always changing, and a few fluctuating forms cause a disproportionate amount of anxiety. The phrase for you and I, in place of the presumed 'correct' form, for you and me, came out top of the complaints in letters written to the BBC about language. Yet several well-known figures have used it in public quite recently, including Oxford-educated Lady Thatcher, who commented that 'It's not for you and I to condemn the state of the Malawi economy.' A surprising mismatch exists between what people condemn and the condemned forms they use without noticing. Perhaps the next generation will shake itself free of this cobweb of pseudo-worries.

The language web, like a spider's web, is woven in a preordained way. As with spiders, time and effort have to go into the weaving process. But humans, unlike spiders, can think about the webs they have woven. This sometimes gives rise to a superfluous cobweb of worries. Ideally, the final layers of a child's web-building would be supplemented by two extra, conscious strands: tolerance of minor variations and an interest in each other's speech.

In Bernard Shaw's play Pygmalion, first performed in 1916, the character Henry Higgins refers to the flower-seller Eliza Doolittle as a 'squashed cabbage leaf, complaining that 'a woman who utters such depressing and disgusting sounds has no right to be anywhere, no right to live'. This narrow-minded view is luckily disappearing. Increasingly, people are beginning to realize that variety is the spice of linguistic life. |

|

|

|

|

Some preschoolers chatter constantly, some run and play incessantly and some sing, dance and perform, basking in the glow of attention. And even if your preschooler is just as happy flipping quietly through books, he's got creative energy just waiting to be unleashed. Consider preschooler-oriented educational toys like puppets, hide-away tents, costume articles for dress-up, easels and art supplies, as well as books that invite imagery or rhythmic speaking.

Some preschoolers chatter constantly, some run and play incessantly and some sing, dance and perform, basking in the glow of attention. And even if your preschooler is just as happy flipping quietly through books, he's got creative energy just waiting to be unleashed. Consider preschooler-oriented educational toys like puppets, hide-away tents, costume articles for dress-up, easels and art supplies, as well as books that invite imagery or rhythmic speaking.