viernes, 8 de abril de 2011

Children and sports

Sports help children develop physical skills, get exercise, make friends, have fun, learn to play as a member

of a team, learn to play fair, and improve self-esteem. American sports culture has increasingly become a money making business. The highly stressful, competitive, "win at all costs" attitude prevalent at colleges and with professional athletes affects the world of children's sports and athletics; creating an unhealthy environment. It is important to remember that the attitudes and behavior taught to children in sports carry over to adult life. Parents should take an active role in helping their child develop good sportsmanship. To help your child get the most out of sports, you need to be actively involved. This includes:

Although this involvement takes time and creates challenges for work schedules, it allows you to become more knowledgeable about the coaching, team values, behaviors, and attitudes. Your child's behavior and attitude reflects a combination of the coaching and your discussions about good sportsmanship and fair play.

It is also important to talk about what your child observes in sports events. When bad sportsmanship occurs, discuss other ways the situation could be handled. While you might acknowledge that in the heat of competition it may be difficult to maintain control and respect for others, it is important to stress that disrespectful behavior is not acceptable. Remember, success is not the same thing as winning and failure is not the same thing as losing.

If you are concerned about the behavior or attitude of your child's coach, you may want to talk with the coach privately. As adults, you can talk together about what is most important for the child to learn. While you may not change a particular attitude or behavior of a coach, you can make it clear how you would like your child to be approached. If you find that the coach is not responsive, discuss the problem with the parents responsible for the school or league activities. If the problem continues, you may decide to withdraw your child.

As with most aspects of parenting, being actively involved and talking with your children about their life is very important. Being proud of accomplishments, sharing in wins and defeats, and talking to them about what has happened helps them develop skills and capacities for success in life. The lessons learned during

As with most aspects of parenting, being actively involved and talking with your children about their life is very important. Being proud of accomplishments, sharing in wins and defeats, and talking to them about what has happened helps them develop skills and capacities for success in life. The lessons learned during

- providing emotional support and positive feedback,

- attending some games and talking about them afterward,

- having realistic expectations for your child,

- learning about the sport and supporting your child's involvement,

- helping your child talk with you about their experiences with the coach and other team members,

- helping your child handle disappointments and losing, and

- modeling respectful spectator behavior

Although this involvement takes time and creates challenges for work schedules, it allows you to become more knowledgeable about the coaching, team values, behaviors, and attitudes. Your child's behavior and attitude reflects a combination of the coaching and your discussions about good sportsmanship and fair play.

It is also important to talk about what your child observes in sports events. When bad sportsmanship occurs, discuss other ways the situation could be handled. While you might acknowledge that in the heat of competition it may be difficult to maintain control and respect for others, it is important to stress that disrespectful behavior is not acceptable. Remember, success is not the same thing as winning and failure is not the same thing as losing.

If you are concerned about the behavior or attitude of your child's coach, you may want to talk with the coach privately. As adults, you can talk together about what is most important for the child to learn. While you may not change a particular attitude or behavior of a coach, you can make it clear how you would like your child to be approached. If you find that the coach is not responsive, discuss the problem with the parents responsible for the school or league activities. If the problem continues, you may decide to withdraw your child.

As with most aspects of parenting, being actively involved and talking with your children about their life is very important. Being proud of accomplishments, sharing in wins and defeats, and talking to them about what has happened helps them develop skills and capacities for success in life. The lessons learned during

As with most aspects of parenting, being actively involved and talking with your children about their life is very important. Being proud of accomplishments, sharing in wins and defeats, and talking to them about what has happened helps them develop skills and capacities for success in life. The lessons learned during children's sports will shape values and behaviors for adult life.

Toys for kids preeschool

Home

Kindergarten Toys

Your child develops many important skills during the first years of schooling, both at school as well as home. Kindergarten toys aid in early education of the child. These

are designed in such a way as to keep the child engrossed, and help in the development of the child’s social skills, gross motor skills and also communication skills. The toys also help in developing the child’s concentration; the more engaging the toy, the better concentration the child will develop. Many of these toys also require two or three children playing together. This serves as a nice way for the children to bond and learn the basic skills of team play.

Kindergarten age kids broadly fall into three categories. The youngest are the four year olds who are yet to develop all the gross motor skills and are a little unsteady in many of the movements. The four year olds form the second category. Four year olds usually attain stability in all their movements and also gain confidence of their motor skills. The oldest are the five year olds. By this age, the kid’s movements are very coordinated and have acquired almost all the motor skills. The classification of the kindergarten children is important as the children of the three categories have different preferences when it comes to toys, as with many other things.

The preference of toys among the kindergarten kids also varies from boys to girls. Girls are usually partial to dolls and dollhouses whereas boys are more fascinated by magnet games, Lego, etc. Children also like simple musical instruments like a small electronic piano. Following are the kindergarten toys that girls and boys like:

Girls like these toys:

· Dolls

· Costumes

· Sorting toys

· Beads

· Craft

· Simple constructions

On the other hand, boys prefer these:

· Magnet games

· Lego

· Wooden blocks

· Simple wooden toys

· Ball games

There are also kindergarten toys that children of all ages, both boys and girls, enjoy equally. These are puzzles, card games, board games, small cycles, etc. When the child’s circle of friends consists of both boys and girls, these toys are the ones that all the friends will enjoy equally.

When buying kindergarten toys, certain precautions must be taken. It is always a good idea to check if the manufacturer has indicated age group for which the toy is suitable. Toys without such indication should be avoided at all costs.

Painting is an activity that kindergarten age kids enjoy a lot. There are many toys where the child is supposed to do paintings with specific colors at specific places. These toys help children discern between colors and is a fun way of learning color names. Don’t let the children use small chalk or crayons though, as they can cause chocking if swallowed. One important thing you should remember is to always supervise kids playing with kindergarten toys.

You can use our product page to find our recommended kindergarten toys. We have selected these toys because they offer kids a great learning experience. When a child has fun, it is easy for them to learn. Playing with these toys goes a long way to the development of your child.

sábado, 26 de marzo de 2011

School objects

Creative Activities with Children

Create a Story Book with Your Child

A fun way to build your child's imagination Writing is still one of our major forms of communication as well as a great way to express ourselves. Creating a storybook with your child is a fun way to introduce him or her to creative writing. You will also get to spend a few hours of quality time together and the end result will become a family treasure for years to come. All you need is a notebook, a pen, and anything else you and your child would like to use to illustrate a story. You can draw pictures together, or make a collage out of old photos and magazine cut outs. Of course you can also add stickers, glitter or anything else you can come up with. But let's start at the beginning. The idea is to come up with a story and to write it down in the notebook. If your child has never made up a story, she will need some guidance and help from you. Think about what she is interested in right now: dinosaurs, ponies, ballet; characters from a particular book or TV show, etc. Ask your child to name the main characters and encourage them to describe what they look like, what clothes they are wearing and where they are. You'll be surprised how quickly they will come up with a story line from there. Encourage them along the way. If your child is old enough to write, have her write the story herself as you go along creating it. Offer to take turns if she is still new at writing. Otherwise, write it down for her. Have fun decorating or illustrating the story. Start your next creative writing afternoon by reading some of the stories you have already created. Give your child the option to either continue with the same set of characters or to come up with some new ones. Before long you will have an entire book of stories that you will both treasure for a long time. ----------------------------------------------------------

| Across1. Use it to add numbers 3. Write with this 5. You can write with this, too. 8. You read this. 9. White and blankDown1. A useful tool for almost anything 2. You measure with this. 4. It writes on the blackboard. 6. A view of the world. 7. Where you sit to write. |

Toys for kids preschool.

PRESCHOOLERS

At preschool age, children tend to be bundles of energy with lots to say and lots more to discover.  Some preschoolers chatter constantly, some run and play incessantly and some sing, dance and perform, basking in the glow of attention. And even if your preschooler is just as happy flipping quietly through books, he's got creative energy just waiting to be unleashed. Consider preschooler-oriented educational toys like puppets, hide-away tents, costume articles for dress-up, easels and art supplies, as well as books that invite imagery or rhythmic speaking.

Some preschoolers chatter constantly, some run and play incessantly and some sing, dance and perform, basking in the glow of attention. And even if your preschooler is just as happy flipping quietly through books, he's got creative energy just waiting to be unleashed. Consider preschooler-oriented educational toys like puppets, hide-away tents, costume articles for dress-up, easels and art supplies, as well as books that invite imagery or rhythmic speaking.

Some preschoolers chatter constantly, some run and play incessantly and some sing, dance and perform, basking in the glow of attention. And even if your preschooler is just as happy flipping quietly through books, he's got creative energy just waiting to be unleashed. Consider preschooler-oriented educational toys like puppets, hide-away tents, costume articles for dress-up, easels and art supplies, as well as books that invite imagery or rhythmic speaking.

Some preschoolers chatter constantly, some run and play incessantly and some sing, dance and perform, basking in the glow of attention. And even if your preschooler is just as happy flipping quietly through books, he's got creative energy just waiting to be unleashed. Consider preschooler-oriented educational toys like puppets, hide-away tents, costume articles for dress-up, easels and art supplies, as well as books that invite imagery or rhythmic speaking.

PLAY FOR PRESCHOOLERSMUSICAL FUN FOR PRESCHOOLERS

STORIES AND POEMS FOR PRESCHOOLERS

TOYS FOR PRESCHOOLERS

This is a dramatic and creative age. Many conversations between preschool-age friends start with "Let's pretend...." Children become social. They become interested in playing with each other instead of preferring to play alone. Many toys become props for cooperative play.

Preschool-age children also are interested in active physical play. They have more control of their muscles at this age and this can be seen in the move from a tricycle to a two-wheel bike. Preschoolers also are increasingly curious about the world around them. They enjoy realistic toys such as farm and animal sets, grocery store prop boxes, model cars, and trains.

As hand coordination increases, so does the child's interest in simple construction sets and more difficult puzzles. They can manage more difficult creative projects, and enjoy cutting and simple sewing projects, in addition to the paint and play dough of earlier stages. Since children at this age also are busy learning to read and write, give them play equipment that encourages these interests.

You may notice that preschool children play with many of the same toys as toddlers, but do so in different ways. As a caregiver, encourage them to be creative and to experiment. There are fewer safety concerns in this stage, but sharp or cutting toys and electrical toys are still too dangerous.

puppets

farm and community play sets

transportation vehicles of all types

simple construction toys

creative materials

books and records

wheel toys

sleds

simple musical instruments

boxes

climbing structures

prop boxes

water play toys

puzzles

balls

cognitive games

dress-up clothes

housekeeping props

dolls and stuffed animals

character toys

farm and community play sets

transportation vehicles of all types

simple construction toys

creative materials

books and records

wheel toys

sleds

simple musical instruments

boxes

climbing structures

prop boxes

water play toys

puzzles

balls

cognitive games

dress-up clothes

housekeeping props

dolls and stuffed animals

character toys

How you can help

1. Get a book on puppets from your local library. Then act out a scene.

2. Act out fairy tales or other children's stories. *The Three Bears*, *The Three Billy Goats Gruff*, and *Caps for Sale* are good starting stories for this. For more ideas on things to do with children and books, see *Good Times with Stories and Poems*.

3. Reverse roles with the child. Let him or her pretend to be the caregiver and you pretend to be the child.

PLAY FOR PRESCHOOLERS

Children who are 4 and 5 are ready for more organized social play. They grow away from being interested only in their own ideas to being interested in the actions and feelings of others.

Preschoolers love to dress-up and pretend. They need dress-up clothes - hats, high heels, purses, play money, or anything grown-ups wear. Providing costumes, dress-up clothes, and equipment or furnishings encourages preschoolers toward creative, dramatic play. Big boxes that can become houses or stores are wonderful. These activities give them a chance to act out their feelings, emotions, and how they view the world about them. This practice of grown-up roles leads to the child's understanding of adults by giving the child a chance to play at being an adult. Preschoolers learn how it feels to be big. They pretend, imagine, create, and imitate what they think it is like to be grown up. They practice relating to their friends. Creative play combines the elements of imagination and fantasy with what is real.

The preschooler learns rapidly through play. Learning the differences in how things feel, look, and sound helps children develop intellectual skills. The child's vocabulary expands through learning about color and size in play activities. As children develop physically through running, jumping, and hopping, they learn action words.

Giving a child an opportunity to get messy also is a learning experience. Playing in mud, sand, and water or painting and coloring gives children a sense of freedom and another chance to strengthen their imagination and creativity. Preschoolers are not lying when they tell wonderful and exciting tales about things that adults know are not true. They are being creative.

MUSICAL FUN FOR PRESCHOOLERS

Children who are 4 and 5 enjoy singing just to be singing! They like songs that repeat words and melodies, rhythms with a definite beat and words that ask them to do things. Preschool children enjoy nursery rhymes and songs about familiar things like toys, animals, play activities, and people. They also like fingerplays and nonsense rhymes with or without musical accompaniment.

If you are caring for preschool children, provide a wide variety of music for them to listen to; folk songs, symphonies, operas, rock and roll, and even sound tracks from movies they might have seen. Suggest that everyone pretend to be animals or objects like cats, elephants, trucks, or bouncing balls, and then imitate these in response to the music. You might provide the children with long scarves with which they can pretend to make butterfly wings. Together, you can move your bodies and "wings" and "fly" along with the music!

STORIES AND POEMS FOR PRESCHOOLERS

Four- and 5-year-olds enjoy stories about things they know. They also like to hear things repeated and enjoy rhythm and rhyme. By now their attention span is more developed and they are able to listen to longer books. You can choose a book with short chapters and read one or two at a time. You might even read a new chapter each time you care for the children.

Preschoolers often memorize words to a favorite book and can "read" the story out loud. They use the pictures as clues to help them remember the words. This is their first step in learning to read. Give them lots of encouragement.

Four-year-olds have a great sense of humor and are curious about people and the world around them. They like to talk and tell "tall tales." They also love silly language, riddles, and non-sense rhymes. Sometimes they will even make up their own nonsense rhymes and exaggerated stories to test their language skills. (They are not "lying", just testing their knowledge of real and pretend.)

Five-year-olds are interested in their families, schools, and neighborhoods, and ask many questions beginning with "how" and "why." Choose books about how things are made or done and why things happen. You may want to think of 5-year-olds as little scientists, always asking questions and testing things out.

Four- and 5-year-olds are forming real friendships for the first time, so stories about friends are meaningful to them. Preschoolers also are beginning to have a sense of rules and justice. They are interested in stories about fairness. They also like stories in which the characters make choices and decisions and get involved in confusing situations. Preschoolers also can learn from stories and poems that portray changes in time since their sense of time is not yet developed.

As a caregiver, it is important for you to remember that 4-and 5-year-olds want to be independent, but still are in need of warmth and security. Books about happy family relationships make them feel good. There are many quality books in libraries and stories today about single parent families, stepfamilies, working mothers, and even grandparents. Be sensitive to the kind of families that the children you care for are growing up in!

Books for Preschoolers

Preschoolers enjoy information books and story books, both realistic and fantasy. Non-fiction books about dinosaurs, insects,rocks, foreign countries, and other subjects that interest them are favorites. They also like realistic stories about their worlds of home and community. Try reading stories about real-life children and places.

The silly language and nonsense of Dr. Seuss books also are perfect for this age. Other favorite topics are first experiences (like a first visit to the dentist), family relationships, funny and wild stories, books about weather and seasons, feelings, nature, and animals.

How you can help

You can help by listening to 4-year-olds' "tall tales" without being critical, and by reading fantasy stories such as *Where the Wild Things Are* to satisfy their yen for the outlandish. You also can help by making an effort to answer 5-year-olds' questions. If you do not know the answer, you may say, "I do not know the answer to that, but let's find a book about it." With the parents' permission, you might plan a trip to the library to find the answer.

To help preschoolers become better thinkers and problem solvers, you can choose stories in which the main character makes a decision. You also can encourage children to talk about or retell stories in their own words and tell you about decisions they have made. Remember how dramatic they can be!

Play silly word games with 4- and 5-year-olds to help develop their language skills. See who can make up the silliest nonsense rhymes. Tell some stories with big words.

Reprinted with permission from the National Network for Child Care - NNCC. Lagoni, L. S., Martin, D. H., Maslin-Cole, C., Cook, A., MacIsaac, K., Parrill, G., Bigner, J., Coker, E., & Sheie, S. (1989). Good times being creative. In *Good times with child care* (pp. 239-253). Fort Collins, CO: Colorado State University Cooperative Extension.

viernes, 25 de marzo de 2011

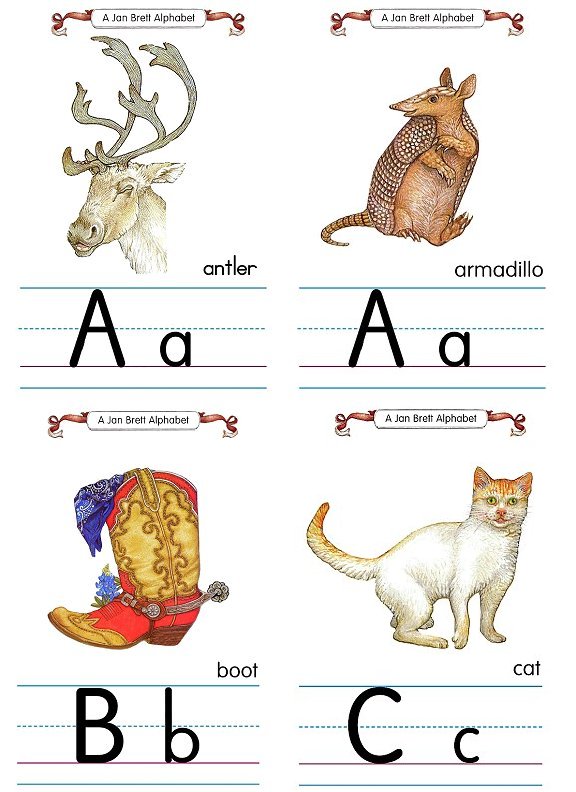

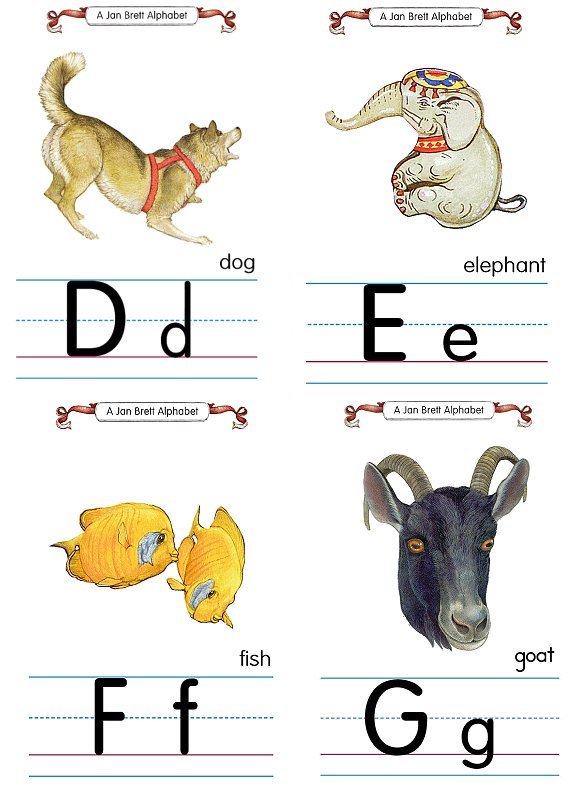

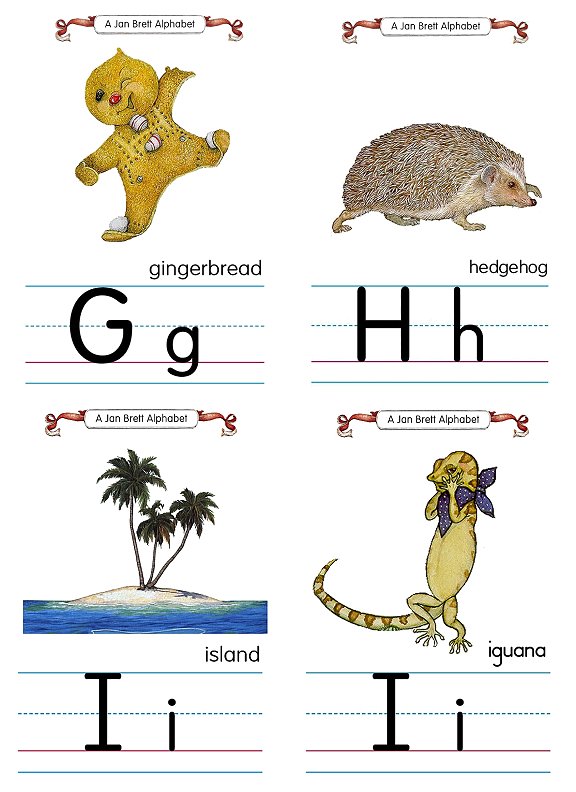

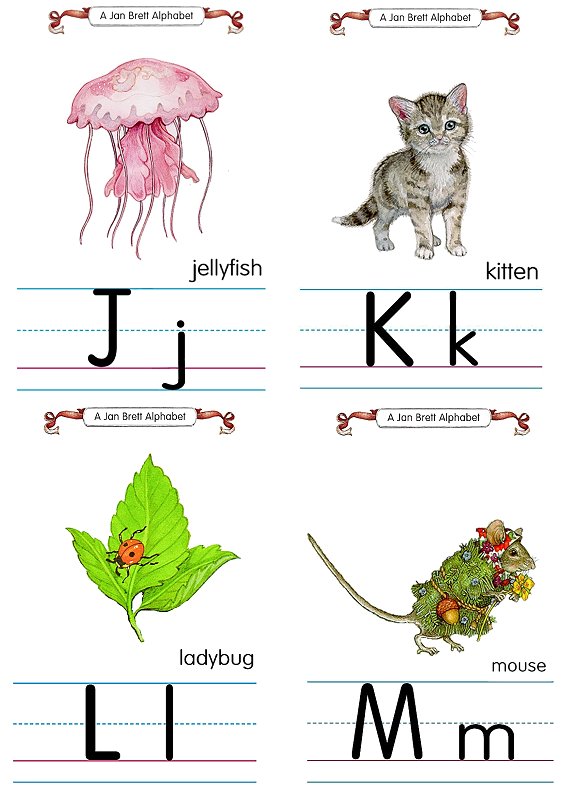

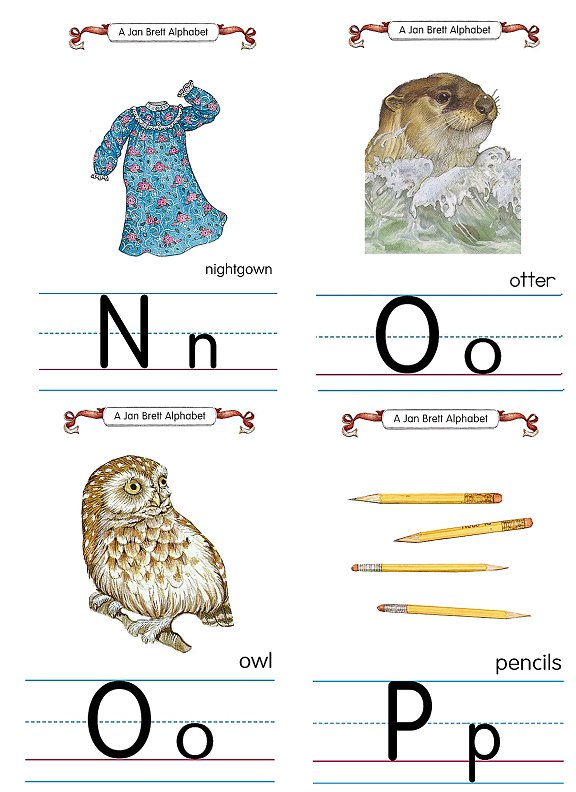

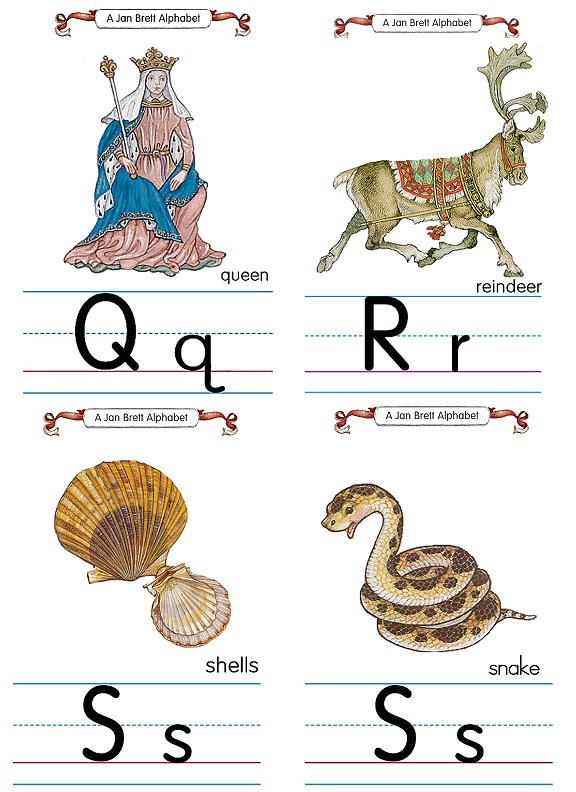

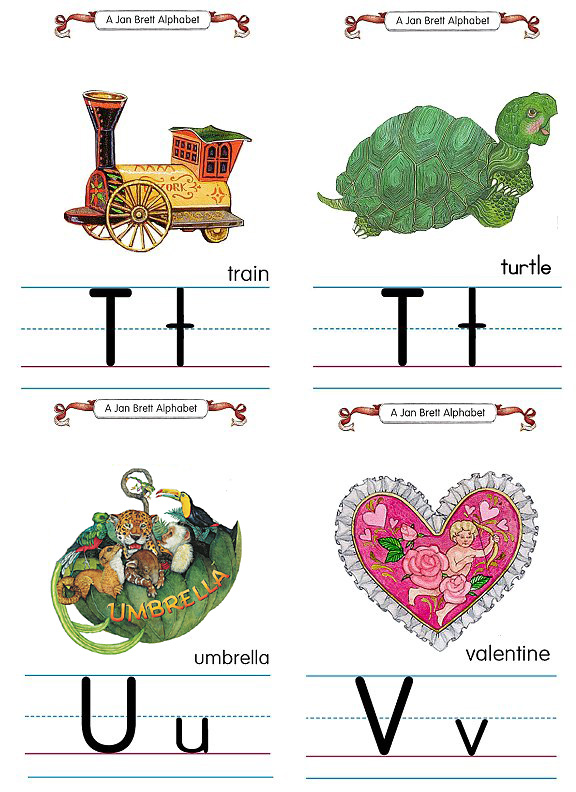

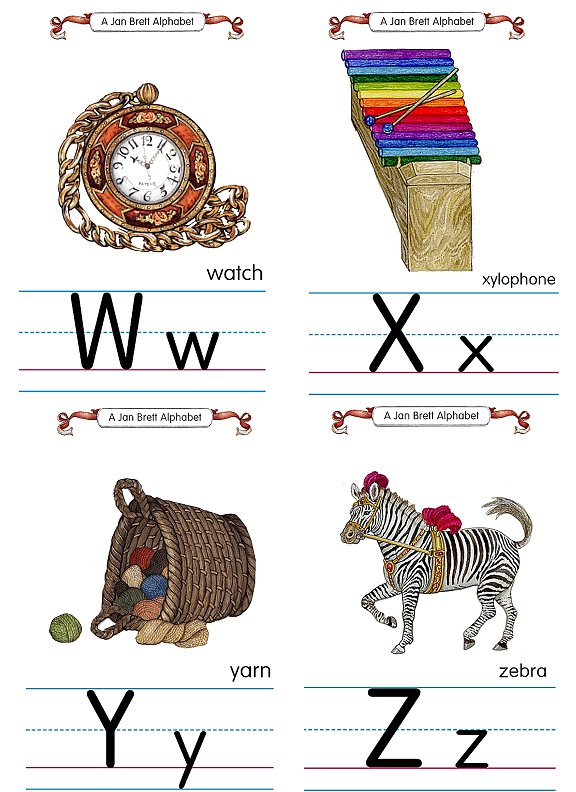

The alphabet for kids.

|

|

|

|

lunes, 14 de marzo de 2011

" Language acquisition

| Learning Objectives | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios (Atom)